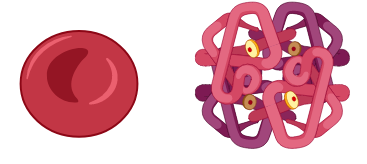

Haemoglobin, found in red blood cells, is the “backbone” of oxygen transportation in the human body. All functional haemoglobins consist of two complementary pairs of globin chains, each containing an iron-packed haem molecule. Haemoglobin A or HbA, a major haemoglobin in normal adults, accounts for about 97% of the total haemoglobin content in red blood cells, while haemoglobin alpha 2, or HbA2, constitutes a mere 2-3%. In minute amounts, many normal adults possess foetal haemoglobin (HbF), the major haemoglobin in foetuses.

The genes encoding the globin chains are located in chromosomes 16 (alpha globin gene cluster) and 11 (beta globin gene cluster).

Haemoglobinopathies

Two abnormalities are associated with haemoglobin. One is due to the production of abnormal haemoglobin (structural haemoglobinopathy), while the other is the reduction or absence of normal alpha (α) and beta (β) chain production. Structural haemoglobinopathies describe structurally abnormal haemoglobins, including E, C, and S. Thalassaemia is classically defined as an inherited autosomal blood disorder resulting in the reduction or absence of one globin chain.

β-thalassaemia

β-thalassaemia is indicated by the lack of the β-globin chains, mainly caused by point mutations or small deletions within the β-globin gene. There is a high prevalence of β-thalassaemia patients, especially in Malaysia, Singapore, and Thailand, due to high β-thalassaemia carrier frequencies among the population. β-thalassaemia can be categorised into thalassaemia minor, thalassaemia intermedia, and thalassaemia major based on their clinical phenotypes. Overlaps among the three groups tend to occur. The clinical phenotypes range from asymptomatic to those who require medical attention, such as regular blood transfusions. For β-thalassaemia major, the clinical manifestations include enlarged liver and spleen, iron overload, growth retardation and having thalassaemia facies due to enlargement of cheekbones and forehead, bone marrow expansion and thinning of the skull. The usual clinical features for β-thalassaemia intermedia include jaundice, spleen and liver enlargement, leg ulcers, and girth expansions.

Over 200 different mutations have been identified in producing the β-thalassaemia phenotype. Each country presents a unique spectrum of abnormal haemoglobins and thalassaemia mutations. Four to five common mutations contribute to about 90% of the thalassaemia population, and a few rare mutant alleles make up the rest.

In Malaysia, thalassaemia is a public health problem among the ethnic Malay and Chinese populations, with ethnic Indians forming the minority among those with the condition. Fortunately, the mutations are classified well according to ethnicity in Malaysia.

β-thalassaemia in the Malaysian population

In Malaysia, ethnic Malay and Chinese constitute the majority of thalassaemia carriers, most of which inherited the Haemoglobin E variant (3-50%). Many of us might not even be aware that different ethnicities in Malaysia carry different types of β-thalassaemia mutations. One interesting fact is that even the indigenous group on the east coast of Malaysia, for example, the Bidayuh, Kadazan and Dusun population, carries some unique thalassaemia mutations that make up the plethora of different mutations that can be found in our country. A great analogy would be to think of the various blood groups we possess, like A, B, AB, and O, together with either Rh positive or negative. This “tagging” similarly applies to the mutations in beta thalassaemia individuals, too!

Treatment for β-thalassaemia

Individuals who are carriers of beta thalassemia usually do not develop symptoms and do not require treatment. However, regular blood transfusions as frequent as every 2-4 weeks will be needed for severe beta thalassaemia cases, more commonly known as beta thalassaemia major, to assist in delivering healthy haemoglobin and red blood cells to the body.

Conclusion

In a nutshell, β-thalassaemia is a common genetic blood disorder in Malaysia. Ethnic-associated mutations may lead to new insights or perspectives on how we view thalassaemia, especially among the general public. Remember to screen for thalassaemia at clinics or hospitals to find out if you are a carrier of this genetic disorder!

Dr Lee Tze Yan is currently a senior lecturer and an active researcher at Universiti Kuala Lumpur. A biomedical scientist by training, he holds an MSc in Molecular Biology and a PhD in Molecular Medicine from Universiti Putra Malaysia. He is interested in science policy and is also an active member of the Young Scientist Network-Academy of Sciences Malaysia (YSN-ASM). He is the honorary advisor for the 8th National Biomedical Science Gathering Malaysia (8th NBSG).