We are all familiar with the Internet, the World Wide Web, or www. Would you believe that, just like us, trees and plants are connected through an underground information superhighway? Trees may look like they are alone in solitary, but they are not alone. They secretly and constantly chat with the other trees and plants around them through an underground “internet” that connects them. They talk to each other, share information, alert each other about danger and even try to kill another tree nearby.

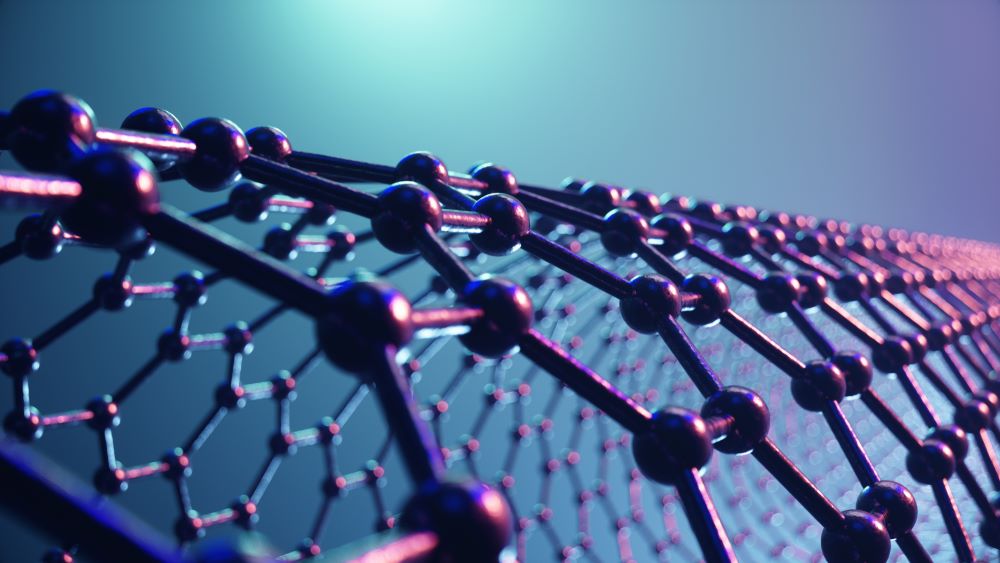

This underground Internet has no routers or modems like ours. Their “internet” is built by fungi or mushrooms. Fungi or moulds grow on our old bread and comprise a mass of thin networks of threads called mycelium. There are soil fungi that grow inside and around the roots of trees. Trees and plants provide fungi with nutrients, especially carbohydrates. On the other hand, fungi send other nutrients like phosphorus and nitrogen through the water the plants absorb. The relationship does not end there.

Fungi build a huge network connecting the roots of nearby trees and plants. It is like our server or telecommunication providers to which we are all hooked and allow us to communicate. It even allows our gadgets to communicate with each other. Similarly, plants and trees are plugged into the network built by these fungi. This is the underground Internet that trees use to communicate with each other. Scientists now call this underground network the wood wide web.

Do trees only talk to among their species? Trees can communicate with those unrelated to them. The mango tree outside your house is probably talking to a nearby hibiscus shrub.

What do trees talk to each other? Trees are constantly helping their neighbours by sharing nutrients. This is probably how older trees feed their seedlings around them. Now we know plants, too, take care of their young ones. A dying tree donates its resources to its neighbours so they do not die in vain, and other trees use their nutrients. Does it sound like humans are donating their organs just before their death?

There are more trees through the Internet. When a tree is attacked by pests such as viruses, insects, bacteria or fungi, the sick tree sends a chemical signal to others through its roots to warn others. This allows the healthy trees to produce chemicals to ward off the pests.

It may sound like a friendly underground environment, but some trees and plants also abuse the wood wide web, just like some people do on the Internet. Fake news, scams and cyberbullying are huge problems on our Internet. On the wood wide web, there is cybercrime, too. Stealing and killing happen among certain trees and plants. The culprits are some types of orchids and black walnut. Orchids steal nutrients from others, while black walnut trees send toxins into the network to kill their rivals. This reduces competition for nutrients, water and light among black walnut trees. These trees are known to harm useful vegetables like potatoes and cucumbers.

Animals are also making use of the Internet. Trees and plants produce chemicals to attract friendly bacteria and fungi to their roots. Some animals, such as insects and worms, can smell these chemicals and look for these tasty roots to eat.

Although some trees and plants can be nasty, scientists say the underground Internet comprises 90% of trees and plants in mutually beneficial relationships. Scientists are still studying this underground wood wide web.

The next time you walk in a park, garden or hike in a jungle, start imagining the underground wood wide web and the chatting and sharing happening beneath your feet. Start looking at trees and plants as friendly organisms constantly sharing good stuff with their neighbours.

There are so many similarities between our Internet and the wood wide web. Trees and plants had their internet millions of years before us. We, too, must learn to live in harmony like them.